After weeks of discussion about the relative benefits of face covering when out and about, ministers have confirmed that it will be mandatory to cover faces in shops in

England and like in Scotland, with those failing to comply facing a fine of up to £100 from the 24th July.

It is quite the shift. At the start of the crisis, the government's scientists suggested that masks could do more harm than good. There were nerves too about creating sudden demand from the public to get hold of medical grade coverings when there was a worldwide spike in demand as the pandemic took hold. But more evidence has emerged about how coronavirus can be transmitted through the air.

Politicians are also keen to find ways to make consumers feel more comfortable going back out into the world, as the economy struggles to come alive again. But things have changed a lot since the start of the lockdown when the government's 'stay at home' message was heard loud and clear.

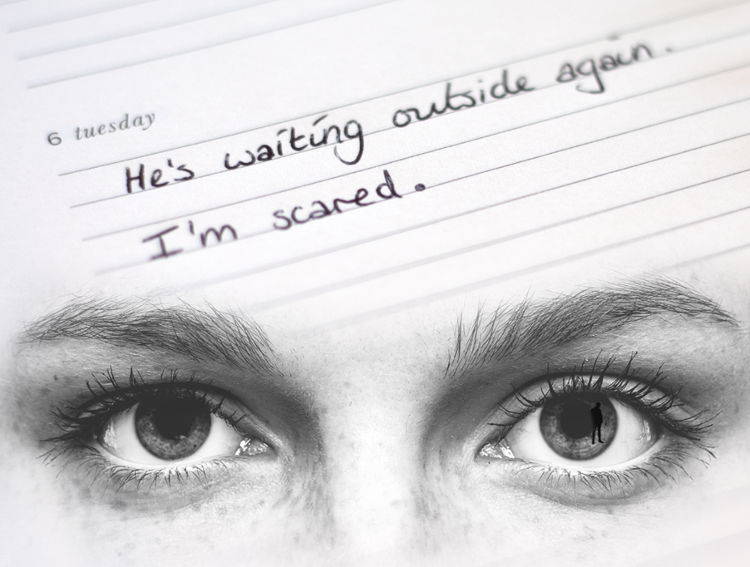

The vast majority of the public stuck to the instruction carefully. Millions tuned into the daily press briefings for the latest information, wanting answers, but wanting guidance too. The expected decision to go ahead on face coverings comes after a scrappy few days when ministers have given different impressions in different interviews.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak appeared without a mask for the cameras serving food. Eyebrows were raised when he was chatting to customers over their vegan katsu without covering his face. The Culture Secretary, Oliver Dowden, did mask up when observing Picassos in the Royal Academy the next day. Then the Prime Minister donned his two quid mask in a recent photo-call.

But Michael Gove made that call for "common sense", and even this morning, the Justice Secretary, Robert Buckland, was saying coverings should be "mandatory perhaps" - a contradiction if ever there were. Clarity, for shops in England at least, should come but you wouldn't be blamed for wondering quite what you are meant to do.

For the government's critics it's another example of ministers playing catch up after allowing confusion to spread. During the early stages of the Covid crisis the public surprised politicians by being very willing to listen and follow the rules.

In this more complicated phase, any hint of a messy message could make them less likely to comply.